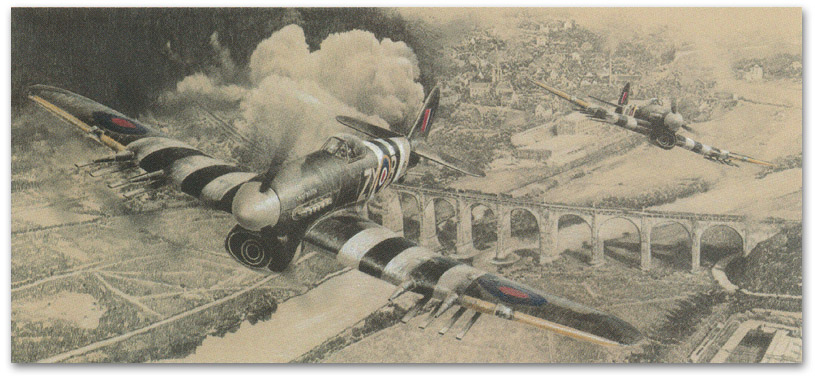

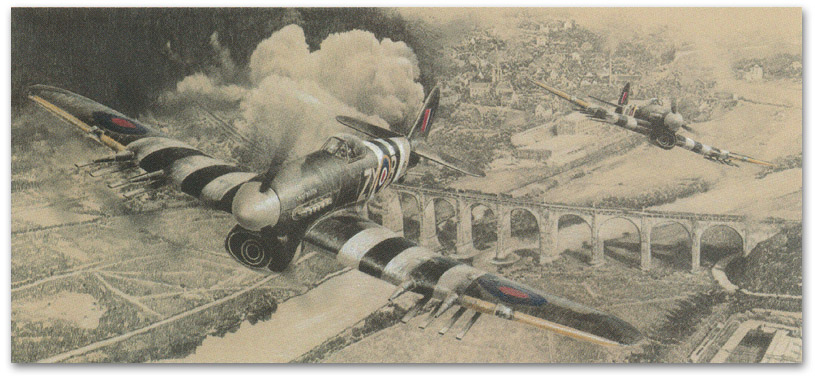

Typhoon Strike

by Richard Taylor

The rugged Hawker Typhoon formed the backbone of the 2nd Tactical Air Force. By D-Day, 6 June 1944 there were 26 RAF, RCAF and RNZAF combat-ready Typhoon squadrons primed to unleash their devastating fire-power on any enemy target that moved; tanks, armoured vehicles and trucks, trains, coastal shipping and E-boats all came to fear the distinctive sound of approaching Typhoons. Airfields, bridges, supply dumps were all targets too. But flying these low-level ground attacks could be a deadly business; more than half of the pilots who flew Typhoons during World War II made the ultimate sacrifice. This dramatic drawing depicts the Typhoon during its finest hour – the battle for Normandy in the summer of 1944. Operating out of a forward airstrip in Normandy as part of the 2nd Tactical Air Force, these Mk.Ib Typhoons from 247 Squadron have just delivered a withering rocket attack on a railway viaduct in northern France a few weeks after D-Day. |

| Overall size: 10" x 15¾" | Available in the following editions |

| 100 | Limited edition | Signed by the artist and Typhoon pilot Bernard Gardiner * | $65 |

| * The regular edition is artist signed only, a handful of prints were additionaly signed by Mr. Gardiner. | |||

| Sold |

| The Signatory |

The Second World War erupted when Gardiner was 18, he volunteered and was sworn in on Oct. 3, 1940, during an enemy air raid in London. He received his initial training in Blackpool and was supposed to be shipped to Canada for more training through the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. However, a German submarine sunk his troop ship, so he was sent to South Africa instead. After acquiring his wings in 1941, he was shipped back to England to train on the Hawker Hurricane. By 1943 the Allies had withdrawn the Hurricane, which forced all pilots to briefly train on the Typhoon. Gardiner converted to the plane, however engineers were still working out glitches, including an engine that regularly seized up, vibrations that broke off the tail, and troubles with the fuel lines. Meanwhile, pilots were told not to fly faster than 527 miles per hour, “Although quite frequently, and in a dive on a target, I saw my airspeed indicator was indicating about 550 mph” Gardiner reported. His first operation found him accompanying his flight commander as his wingman. As his leader fired on enemy positions below, Gardiner’s plane flew through a cloud of expended ammunition shells that stuck to his wings. This didn’t impress his flight commander, so Gardiner joked that he never flew with the man again. By 1944 the German air force had all but disappeared, so Gardiner rarely saw enemy planes. The only aircraft he saw and attacked was a flying boat attempting to take off from a bay.“And with a squadron of war-hungry Typhoons above, that was a rather foolish operation. It was his very last flight,” stated Gardiner. During the initial invasion phase, Gardiner’s squadron provided close support glider-towing C-47s. Later, Gardiner’s unit began bombing railway lines in the Netherlands that were being used by the Germans to transport V1 “doodle bugs” and V2 rockets to the coast before being launched at London. The squadron also worked to knock down V-1s by flying in front of them and interrupting the autopilot. “It would lose control and spin and crash to the ground, hopefully without causing too much trouble down there,” recalled Gardiner. Gardiner’s last mission was on May 3, 1945. |